Weber Media Partners | Impressions Through Media

Conversational Marketing in the Age of Social Media

- Home

- About This Blog

- Contact

- Sitemap

How Social Media Enabled Egypt’s Revolution: Part Two

Author: Theresa Grenier1 Jul

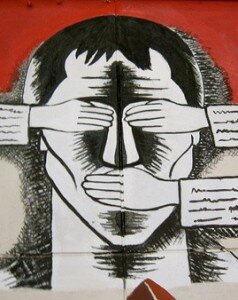

Two Can Play at this Game: World Governments’ Responses to Social Media as a Revolutionary Tool

In the first part of this series, we explored how social media enabled and facilitated Egypt and Tunisia’s revolutions. By using Facebook and Twitter to broadcast their beliefs, find like-minded individuals the world over, and organize protests in near real-time, the revolutionaries were able to stay one step ahead of their governments. But now, it seems, the governments are catching up.

In the first part of this series, we explored how social media enabled and facilitated Egypt and Tunisia’s revolutions. By using Facebook and Twitter to broadcast their beliefs, find like-minded individuals the world over, and organize protests in near real-time, the revolutionaries were able to stay one step ahead of their governments. But now, it seems, the governments are catching up.

In Egypt, segments of the government and army are now on Facebook, using it as a means to spread their own propaganda and to keep an eye on known activist communities. At one point during the revolution, the Egyptian government even shut down internet access, fully aware of the threat it posed to the government. Amr Abouelleil, an Egyptian-American bioinformatics analyst and writer who is actively involved with the Egyptian Youth Movement at the heart of the revolution, says the government was aware that without the internet, people would have to turn to state television (which is government-censored) for their news. The government used this opportunity to up their ante, broadcasting pro-government programming to the unwired masses, which in many cases, appeared to work. “The government got some people to change their tune in just a matter of days,” Abouelleil says. “It brainwashed them to go back on Facebook in the government’s favor instead.”

Egypt is not the only government in fear of the power social media and the internet provides its people; when Google reportedly foiled an alleged Chinese attempt at stealing the passwords to hundreds of Google accounts, including those of government officials, Chinese human rights activists, and journalists. The Chinese government has since denied involvement, but is well known for their censorship of the internet and television. Whether or not the government is responsible for the hacking attempt, it’s safe to say that they are well aware of the power of the internet and social media, and doing all they can to control it.

Government reactions to the use of Google and social media have been so extreme in recent months that Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt has said he fears for the safety of Google employees in certain parts of the world. “There are countries where it is illegal to do things that Google encourages. In those countries, there is a real possibility of (employees) being put in prison for reasons which are not their fault,” Schmidt told attendees of Google’s Dublin summit on militant violence this past Monday, June 27.

A prime example of this is Wael Ghonim, the Egyptian Google executive who is now one of TIME magazine’s 100 most influential people of 2011. Ghonim was held captive by the Egyptian government for eleven days in early 2011 due to his involvement in using Facebook to organize protests via a page called “,” which exposed and raised awareness of the military’s cruel and inhumane murder of Khaled Saeed.

Saeed was a 28 year-old Egyptian resident who was arrested by Egyptian police at an outdoor café and then publicly beaten to death in so brutal a fashion that he was nearly unrecognizable after. “We are all Khaled Saeed” quickly became Egypt’s biggest dissident Facebook page, and the pressure it put on the government was so intense that the government ultimately agreed to put the two arresting officers on trial. The trial, scheduled to end yesterday, June 30, was just postponed for the second time. A verdict is now expected to be announced in September.

Scott Shane, in an article for The New York Times, reinforces Schmidt’s fears, saying that governments’ increasing awareness of the role of social media in revolution is, in fact, causing them to begin mining the internet for revolutionary stirrings and getting a leg up on the revolutionaries. He says that in Belarus, K.G.B. officers now routinely troll activists’ comments on Facebook and will use them as evidence or intelligence in and for interrogations. He cites Alexander Lukashuk, director of the Belarus service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, as saying how a Belarusian photojournalist was recently caught at home in the morning and interrogated by the K.G.B. after she had written that the K.G.B. usually conducted their searches at night.

Syrian activist Ahed al-Hindi tells Shane that “Facebook is a great database for the government now.” He believes that while Facebook is doing “more good than harm,” it does allow oppressors a window into activists’ plans and activities. As Widney Brown, senior director of international law and policy at Amnesty International says, “[social media] can be used to promote human rights or to undermine human rights.”

As long as revolutionaries are aware of this, we believe that social media will continue to help mobilize change. In Egypt, they are already making contingencies for the government’s monitoring of the Web, and in some cases, going “old-school,” as Abouelleil calls it. In late January, an anonymous 26-page leaflet was circulated among protestors in Cairo providing practical and tactical advice for mass demonstrations, dealing with riot police, and laying siege to and taking control of government offices. The leaflet instructed that it only be passed on by email and photocopy, but not by Facebook and Twitter, as they believed them to be monitored by the government.

Despite the growing awareness by governments on the use of social media as a revolutionary tool, we have little doubt that, with a little craftiness, activists will continue to use it as a means to organize protests and let their voices be heard. As Abouelleil says, “When Tunisia happened, it gave people hope, and they lost their fear. I don’t think the people organizing this revolution are afraid anymore. They don’t care if the government knows; of course they know, but what are they going to do? There are a million people there.” And as the message continues to go out via social media, more people join the cause every day.

For more on social media and the revolution in Egypt, check back next week for the third and last installment in this series, where we’ll speak further with Amr Abouelleil and get his insider’s view as to just how social media was used in Egypt’s revolution, what Egyptians and Egyptian-Americans thought of it, and what’s to come as the country begins to rebuild.

Image: Gigi Ibrahim via Flickr

- RSS feed for comments on this post

- TrackBack URI

- Subscribe To Feed (RSS)

- Comments (RSS)

- Subscribe via Email

One Response for "How Social Media Enabled Egypt’s Revolution: Part Two"

[...] Part 2 is now up. Two Can Play at this Game: World Governments’ Responses to Social Media as a Revolutionary Tool [...]

Leave a reply